Born to Hunt. Wayne Tillerson, Venus, and the Platonic Forms

In season 1 episode 2, we are treated to an exceptionally performed scene by Will Patton. Wayne Tillerson apprises Royal of a period in his life in which he fervently acquired a collection of erotic art for his home. This scene seems to serve dual purposes. One, it connects Wayne to the notion of eroticism. It won’t be the last time his character mentions sexuality. This is a clue to his connection to Greek mythology, as of course is his perennial consumption of clam juice. Secondly, this marks the first moment in the show that hints at a higher order of knowledge and our pursuit of it through our earthly senses.

Wayne’s account of his hunt for the perfect erotic painting is an allusion to the Platonic creative ascent, as discussed in Plato’s Symposium and the Timaeus, in which human beings strive to understand The Forms by experiencing shadows of them in waking life. We can never truly experience perfect beauty, love, or indeed eroticism, and yet we constantly search for experiences or objects that get us as close as possible to these perfect, unattainable ideals.

The scene is foreshadowed as Royal waits in the living room and stares up at Wayne’s collection of stuffed owls. We learn later that they are each named after a Platonic Form: Prudence, Integrity, and one named Luke, ostensibly an alias for Brotherhood. Or, it could possibly hint at Luke being a manifestation of a Form, perhaps Ambition.

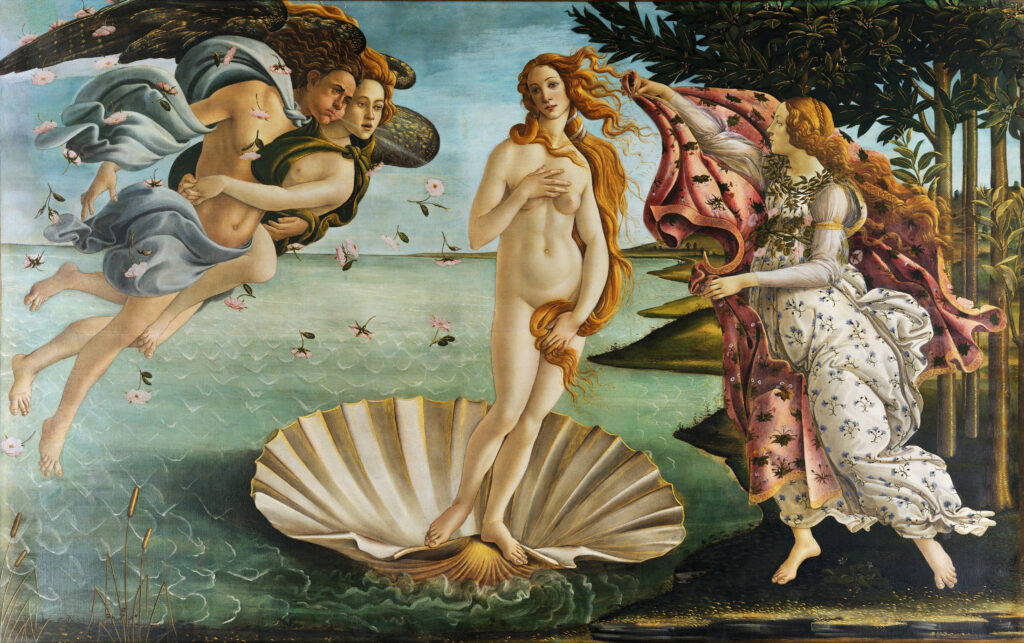

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus blurs the frontier that divides the two sides of our nature, body and soul, in order to overcome their contradictions—and thus reconcile us with the unity of the cosmos.

Herman, Arthur. The Cave and the Light (p. 388). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

The most important classical painting relating to Outer Range is undoubtedly The School of Athens, by Rafael, but we will save this analysis for another post. This scene seems to be strongly influenced by The Birth of Venus, by Sandro Botticelli. It depicts the goddess Venus being called forth from the realm of The Platonic Forms atop a giant clamshell. The theme of the painting is drawn directly from Plato’s Symposium. Plato argued that the earthly appreciation of physical beauty, or even simple lust, was a pathway to understanding The Form of beauty. Plato names Venus specifically in this work.

Here is an excerpt from The Cave And The Light, by Arthur L. Herman:

“Like the Graces and Spring, The Birth of Venus is arranged in a triad. On one side are the “passionate winds”—zefiri lascivi, Poliziano calls them—symbolizing the power of love at its carnal starting point, the passionate frenzy of Eros. On other side is the allegorical figure of

Spring again, clothed, and looking very self-contained as she offers a cloak to the nude Venus. Physical profane love is transformed into chaste divine love, the endpoint of the Platonic creative ascent—just as the face of Botticelli’s Venus dissolves into his depictions of the Virgin Mary. Sexual desire carries the seed (literally) of its spiritual opposite; in a profound sense, they are indistinguishable. Through love we find the highest even in the lowest (as the Pseudo-Dionysius might say): perfection in imperfection; or harmony where others see discord. Ficino even claims that in the Timaeus, Plato locates Love at the very heart of the primeval Chaos from which cosmic order will emerge.18 As inspired by Ficino, Botticelli’s Birth of Venus blurs the frontier that divides the two sides of our nature, body and soul, in order to overcome their contradictions—and thus reconcile us with the unity of the cosmos”

– Herman, Arthur. The Cave and the Light (pp. 387-388). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

From wikipedia:

For Plato – and so for the members of the Florentine Platonic Academy – Venus had two aspects: she was an earthly goddess who aroused humans to physical love or she was a heavenly goddess who inspired intellectual love in them. Plato further argued that contemplation of physical beauty allowed the mind to better understand spiritual beauty. So, looking at Venus, the most beautiful of goddesses, might at first raise a physical response in viewers which then lifted their minds towards the godly.[29] A Neoplatonic reading of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus suggests that 15th-century viewers would have looked at the painting and felt their minds lifted to the realm of divine love. – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birth_of_Venus

In episode four, Wayne is given a rock with the time mineral imbedded in it from his worker. Note the similarities to Wayne and Venus as he holds the rock to his breast and sings.